Introduction

What role, if any, does spirituality play in the leadership practices of educators and why is this an important topic for study? Spiritual leadership has been defined as a type of leadership characterized by defending integrity, goodness, teamwork, knowing, wholeness, and interconnectedness (Aydin & Ceylon, 2009). Pio & Lengkong (2020) discovered increased spiritual leadership significantly influenced ethical behavior; and higher values of spiritual leadership resulted in higher ethical behaviors. “The relationship between spiritual leadership to quality of work life and ethical behavior and its implication to increasing the organizational citizenship behavior” (pp. 293-305) may demonstrate a correlation with the spiritual practices of educational leaders. The praxis of spiritual leadership by leaders may significantly influence and impact human behavior within their organizations. This impact upon people and their behaviors underscores the importance to study and better understand this influential phenomenon of spiritual leadership.

Diverse perspectives and personal experiences make the study of spiritual leadership complex; however, despite the complexity, through an examination of spirituality as a leadership practice of principals in public schools of what they do as leaders may be significantly influenced by who they are as people and have a greater impact on workplace behaviors. To determine who they are, leaders may undergo a process of self-awareness to help them discover the various layers of their own leadership identity that encompasses behavior, interpersonal skills, attitudes, values, beliefs, and assumptions (Stebbins, 2021). However, spirituality is not to be construed as religion.

Importantly, spiritual leadership is not workplace religion. Rathee & Rajain (2020) explained that workplace spirituality is not the same as workplace religion. “Working in an environment that supports the employees’ right to openly express their beliefs helps them to have better working relationships with colleagues, feel safer, and be more engaged in their work” (p. 27). Although the term spirituality has various connotations often interconnected with religion, for this article, the concept of spirituality will transcend denominational doctrine and practice. An in-depth study of the role of spirituality in leadership as soulful leadership may be used as a reflective lens for deeper understanding and value.

In seeking to understand the relationship between leadership and spirituality, a review of the literature has shown that spiritual leadership is worthy of additional study. The literature on leadership is quite extensive, but there is only a narrow focus upon the relationship between leadership and spirituality or among the spiritual leadership of school principals. Dent et al. (2005) analyzed studies exploring the symbiotic relationship between leadership and spirituality: “Leadership and spirituality are two pervasive constructs in life, and a greater understanding of how they interrelate may do much to increase the welfare of the workplace, humanity, and the environment” (Dent et al., 2005, p. 648). More specifically in a study of school leaders, Zaharris et al. (2017) discovered that principals often “balance the tensions inherent in the pursuit of desired school goals with the need to prioritize the well-being and care of the human spirit” (p. 82). Interestingly, their study also uncovered a substantial increase in the study of spiritual leadership within the past 20 years.

Robinson (2011) conducted a large-scale study of the impact of campus principals as school leaders and school achievement in his identification of five categories of leadership that included: establishing goals and expectations, resourcing strategically, ensuring quality teaching, leading teacher learning and development, and ensuring an orderly and safe environment. Similar categories were explored throughout existing leadership literature in the area of school improvement and the influence of principals. This body of research defined a set of actions demonstrated by effective principals during the course of their campus-level leadership, but did not address the spiritual leadership of school leaders. “Although some may consider the topic of spirituality unworthy of scientific study, the power it contains to transform traditional thinking about leadership is well worth the academic risk” (Zaharris et al., 2017, p. 82). The literature emphasized the importance of understanding the relationship between spirituality and leadership, yet demonstrated a lack of research when examining this synergistic relationship within schools.

Problem Statement

As school districts continue to meet the complex demands of educating students, there are increasing expectations from principals and teachers—implement more, assess more, intervene more. The time and emotional investment of continuing to do more will eventually lead to an organizational implosion (Reeves, 2006). Leaders and teachers alike eventually reach the burnout stage. “Not only will the new initiative fail under such circumstances, but the energy and resources available to old and continuing initiatives are dangerously compromised as well” (Reeves, 2006, p. 108).

Merely doing more does not lead to improved outcomes, although systems intended to support principals often encourage just that—do more. Despite these actions, instructional leaders try to maintain their focus, avoiding the allure of more money and high-profile initiatives (Fullan, 2014). Pink (2009) described the drive behind actions in three parts: autonomy, mastery, and purpose, stating that “Autonomous people working toward mastery perform at very high levels. But those who do so in the service of some greater objective can achieve even more” (p. 133). Thus, systems designed to develop principals should empower them with the freedom to identify a focused set of initiatives and provide the support to implement those initiatives with mastery. However, principal development is incomplete without helping these leaders understand how beliefs about the human spirit give purpose to their actions (Pink, 2009).

Research Questions

In seeking to answer the critical question of who leaders are and how this influences what they do, the authors conducted an empirical qualitative research study in the fall of 2021. The purpose of this study was to define, in terms of both words and actions, the characteristics of spiritual leadership in schools, and principals’ perceptions of the role spiritual practices have in creating a campus culture that influences the behaviors of others. Principals from school districts within a regional area of Texas were selected for this study. The descriptive data gathered from interactions and interviews reflected their perceptions of leadership as a spiritual practice in terms of reflective practices, actions of the leader, and behaviors of others. An analysis of the principals’ responses defined the characteristics of spiritual leadership among school leaders, and follow-up interviews uncovered how leaders described the relationship of spirituality with leadership. The research study answered the following questions:

-

According to school principals, is leadership a spiritual practice, and if so, to what extent?

-

What are the affinities (categories) of spiritual practices among principals?

-

What is the relationship between these affinities and leadership actions?

-

How do principals perceive the influence of spiritual leadership upon the behavior of others?

Literature Review

Research on leadership as a spiritual practice is abundant in peer reviewed articles dedicated to the topic. The organization of this review narrowed the focus to three areas of study: 1) understanding the complexities of the idea of spirituality, 2) the role of spirituality in leadership, and 3) an investigation of the current research in spiritual leadership practices found in schools. One central pattern of thought became clear in reviewing the literature. Several academic writers suggested that spirituality is an important topic worthy of study in the increasingly troubled world in which we live.

Understanding Spirituality

Given the interest in spirituality, the literature included numerous studies dedicated to the difficulty of defining the term. The complications in defining spirituality often arose from personal experiences with the concept. For example, the relationship between spirituality and religion was the object of a mixed-method study by Schlehofer et al. (2008) designed to determine how the public differentiates between these terms. Interviews with older adults found that religion and spirituality are often used synonymously (Schlehofer et al., 2008). Although the terms are often seen as the same, distinguishing between the two is important. One meta-analysis concluded that religion described a specific group or organizational structure, while spirituality was often associated with closeness with God, feelings of interconnectedness with the world, and sometimes even incorporating more than one religious’ approach (Zinnbauer et al., 1999). Researchers have been careful to distinguish between the two terms when studying spirituality related to the workplace. As described in the literature, this study separated the two terms, and employed a definition of spirituality that remains agnostic to religious affiliations.

Another layer of density arose when studying the value ascribed to one’s spirituality within the similar field of social work. Senreich (2013) described the issue of people being seen as “more” or “less” spiritual. When value is granted to a person based on their viewpoint of something relatively indefinite, such as spirituality, the foundations of social work education break down. The cornerstone of inclusiveness is diminished when priority is given to certain perspectives (Senreich, 2013). In contrast, Fry (2003) described “membership” as a foundation of spirituality, stating that “organizational culture be based on altruistic love whereby leaders and followers have genuine care, concern, and appreciation for both self and others, thereby producing a sense of membership and understood appreciation” (p. 695). Spirituality, in and of itself, is inclusive.

Dames (2019) connected the idea of spiritual membership beyond the human connection; spirituality connects people through a common higher purpose. “Spirituality is a search for and means of reaching beyond human existence. It creates a sense of connectedness with the world and with the unifying source of life […] an expression of people’s profound need for coherent meaning, love, and happiness. The need to create coherent meaning (in terms of wholeness, fullness, ultimacy) is inherent for our very existence as human beings” (Dames, 2019, p. 39).

Spirituality and Leadership

In a review of over 150 studies, Reave (2005) found a clear consistency between spiritual practices and effective leadership. Spiritual ideas such as integrity, honesty, and humility overlap with crucial leadership skills (Reave, 2005). Studying spirituality and leadership is important not only because of the common attributes, but also because “a greater understanding of how they interrelate may do much to increase the welfare of the workplace, humanity, and the environment” (Dent et al., 2005, p. 648). Decision-making is elevated when leadership and spirituality interrelate. Hermans & Koerts (2013) defined spirituality as discernment: “Discernment is a human capacity for making decisions that promote human fullness” (Hermans & Koerts, 2013, p. 207). Studying the confluence of effective leadership practices and spirituality may uncover a new philosophy of leadership. Noghiu (2020) introduced this idea in a framework for spiritually infused leadership, stating, “Spiritual worldviews are more likely to present fundamental and creative alternatives to many current leadership ideas (such as competition, zero-sum thinking), raising spirituality to a leadership and organizational advantage” (p. 57).

These findings associated with spiritual leadership created direction for a new leadership paradigm. For example, in the area of business education, there are now more than 30 Masters of Business Administration (MBA) programs offering courses in spirituality in the workplace for future leaders (Phipps, 2012). Development of future leaders was, on one level, a matter of intelligence. Sidle (2007) identified five archetypes of intelligence: action, intellect, emotion, spirit, and intuition. The key to unlocking leadership potential was helping leaders find a balance across multiple intelligences, including spiritual intelligence (Smith & Gage, 2016). Although Smith & Gage (2016) did not assign a hierarchy to the types of intelligence, Zohar (2005) made a case for spiritual intelligence, a leadership intelligence that focused on a higher purpose, being the ultimate intelligence, and was the form of intelligence demonstrated by leaders “like Churchill, Gandhi, and Mandela” (Zohar, 2005, p. 60). Great leaders throughout history have been called upon to lead through troubling times. This type of leadership required leaders to find an inner security that lies in their spiritual intelligence (Smith & Gage, 2016). “Leader’s spiritual beliefs, activities, and practices should provide promising new ways to understand how leaders transcend and progress through the stages of human development” (Dent et al., 2005, p. 648). Effective leaders and spiritual practices do share common attributes; however, it is a leader’s spiritual intelligence or leading with a higher purpose that differentiated leaders and predicted leadership effectiveness (Wigglesworth, 2006).

Spiritual leadership was most effective when tasks lacked certainty. During uncertain times, spiritual leadership enhanced team effectiveness by helping workers find value, purpose, and significance in their work (Yang et al., 2019). Pawar (2014) further supported this finding that subordinates of spiritual leaders felt cared for, concerned about, carefully listened to, and recognized for contributions. However, the study of spirituality and strategic leadership did raise caution, particularly when examining the interpersonal aspects of spiritual leadership. Phipps (2012) questioned the level of analysis possible concerning the complex relationships between the leaders and subordinates throughout an organization. Researchers found that spiritual leadership may be used as a management tool to pry into personal lives (Bell & Taylor, 2003). Additionally, Lund Dean & Safranski (2008) advised against “managing” or manipulating an employee’s spiritual energy at work. Contrarily, an alternative was to maintain a work environment that was open to reasonable levels of spiritual expression.

Yet, despite the concerns, spiritual practices of both the individual and collective continued to be “encouraged as part of day-to-day work life as a way to energize behavior in employees based on meaning and purpose rather than rewards and security” (Konz & Ryan, 1999, p. 627). Motivation of a spiritual leader played a critical role in understanding actions and potential risks. According to the literature, leadership grounded in spirituality tended to lend an intrinsic meaning to life (Fry et al., 2017). Further, Fry et al. (2017) defined extrinsic motivation as effort driving performance that was rewarded, that is, the greater the reward the more the effort. Alternatively, a definition of intrinsic motivation was offered as effort driving performance, where the result of the work was the reward (Fry et al., 2017). Leaders, particularly spiritual leaders, who are motivated by the results of the work, shared inherent risks. Cregård (2017) published a study examining the potential personal risks of spiritual leaders and warned against “the demands of limitless care and love (empathy) and personal sacrifice, which might result in work overload” (Cregård, 2017, p. 540). In this study of spiritual leadership, researchers noted that there was little, if any, extrinsic reward for the personal sacrifices of leaders, so the risk of overload was highly possible for leaders who were often intrinsically motivated. Therefore, the balance of risk and reward was important to understand.

Spiritual Leadership in Schools

Leadership practices of the principal is critical to success in schools (May et al., 2012), and this study sought to examine how spirituality informs leadership practices. The literature specifically focused on spiritual leadership in schools was limited. School leadership was analyzed from a technical perspective related to the functionality of running a school. Foster (2004) concurred by stating that “the language that has generally contoured school leadership has often been a functionalist positivistic and technical language oriented largely to modernist issues” (p. 178). The role of the modern principal required a new pattern of language. According to Dantley (2010), principals leading learning communities involved more than rational, value-free techniques, and empirical accountability. Dantley (2010) proposed an alternative language of servanthood, purpose, and personal reflection, believing that by shifting the language, the field of education could move beyond the limits of the current educational landscape. This shift in the language may “welcome the totality of self, in particular, the inclusion of the spiritual self” (Dantley, 2010, p. 218).

As the executive leader of a campus responsible for the well-being of children throughout a community, the job of being a principal can be emotionally taxing. Elmeski (2015) pointed to spirituality as an anchor for principals, crediting core spiritual values for keeping their “leadership spark alive” (Elmeski, 2015, p. 10). If spirituality ignites the spark, bureaucracy can seek to extinguish that spark. Dantley (2015) attributed spirituality with “broadening leadership beyond the parameters of hierarchical duty to one of impacting the transformation of societal forms and rituals through the educational process” (p. 440). Gibson (2014) went a step further with a case study of lived experiences of spiritual principals, finding the following:

[…] integration of their spirituality perspectives helped them sustain positivity in the challenging and stressful role of principal leadership, by providing inner strength and a strong sense of purpose. For example, spirituality was believed to help them have a hope for the future, to see the potential in children, and to have a positive disposition in the face of significant educational and social challenges (Gibson, 2014, p. 528).

This held true not only for the principal, but also for the membership of the campus. Stylianou & Zembylas (2019) encouraged principals to think on a higher, spiritual level because of the potential of creating a more inclusive campus. When spiritual behavior was emphasized, staff felt part of a family environment in a school (Özgenel & Ankaralıoğlu, 2020). A level of influence was achieved when spirituality was shared, as the ideals permeated and elevated the campus as an organization. Rocha & Pinheiro (2021) shared that when individual spirituality aligned, organizational spirituality thrived. Individual spirituality enlightened the purpose of life; thus, organizational spirituality created social good (Rocha & Pinheiro, 2021).

Spiritual leadership may be developed through personal and professional experiences that shape knowledge, emotions, and virtues (Woods, 2007). The awareness gained through spiritual development opportunities shaped an individual’s spiritual well-being, that was believed to be predictive of leadership behaviors (Mehdinezhad & Nouri, 2016). Mehdinezhad & Nouri (2016) found that principals who were spiritual leaders were the first to come to school every day, shared breakfast with students and staff, encouraged direct communication, substituted for teachers, and shared leadership responsibilities. Woods (2007), Mehdinezhad & Nouri (2016), and Luckcock (2008) agreed that programs designed to develop spiritual well-being should be a foundational component of leadership development.

Spirituality connected people around purpose. Aspects of effective leadership and spirituality were interrelated and unlocked new levels of leadership potential when truly understood. Although the literature in school leadership setting was less robust, a clear pattern did emerge. Spiritual leadership in schools may be developed through meaningful interactions and has the potential to create hope, form community, and maintain focus on the higher purpose and reward of the work.

Method

The methodology for the qualitative research chiefly involved the use of Interactive Qualitative Analysis (IQA). Bargate (2014) investigated the use of IQA as a method for qualitative research and reported, “What sets IQA apart from other forms of qualitative inquiry is that it provides an audit trail of transparent and traceable procedures where the constituents, and not the researcher as expert, do the analysis and interpretation of their data” (p. 11). IQA is based on the idea that those closest to leading a campus, i.e., principals, were most suitable to analyze the data. Schlehofer et al. (2008) reinforced the marriage of IQA and studies on spirituality through their conclusion that it might be fruitful to ground the definition of spirituality, at least partially, in the lay definitions from the population of interest (p. 423).

Initially, the principals analyzed focus group data during a collaborative process to construct categories of meaning based on commonalities or affinities. This process was conducted in a collective setting, to allow for collaboration among the principals, with the researchers acting as facilitators for the analysis (Bargate, 2014). The affinities developed by the principals provided the protocol for semi-structured interviews, wherein the principals’ experiences were explored further. IQA was a method where the participants were empowered to do more than just generate data, and the researchers were not considered to be the only persons knowledgeable enough to analyze the data. Thus, this study was conducted within the collaborative approach of IQA.

Participants

Leaders invited to participate in this study consisted of 94 campus principals within a 30-mile radius of a regional university in Texas. This included every principal of a public school in the identified area. The geographical area in this study had a few, small private schools with non-traditional leadership structures; therefore, for the purposes of this study, private schools were excluded. Participants were recruited through an email invitation to complete a survey. They answered one question and indicated willingness to participate in two additional protocols—an in-person data analysis focus group and a one-on-one interview. Principals indicating a willingness to continue participation were invited to continue. The data analysis focus group and interview protocols took place within four weeks of the closing of the survey.

Although this study intended to survey 94 campus principals, the assistant superintendent of one district requested that their principals be excluded from the study, stating that the topic of this study lacked direct and actionable feedback about instruction and student performance. Due to this request, study participation was reduced to 38 campus principals. Of this group, 27 principals completed the survey. Twenty-three principals indicated strongly agree or agree that spirituality played a role in leadership practices and expressed willingness to participate further in the data analysis process. Ultimately, 14 principals participated in the data analysis focus group, and ten of those principals completed the follow-on interview.

Research Design

This qualitative research design methodology included surveys, focus groups, and interviews as the main sources for data collection. The data collection and analysis procedures are outlined below.

- Survey

- Data Analysis Focus Group

- Silent Nominal Group Technique

- Open and Axial Coding

- Identifying Research Affinities

- Developing the Affinity Relationships

- Interviews

Surveys

Public school principals within a 30-mile radius of West Texas A&M University were invited to complete an online survey consisting of two questions. The first question was constructed based on a five-point Likert scale for agreement, that measured the extent the principals felt that leadership was a spiritual practice (1: strongly agree to 5: strongly disagree). The second question was used to identify those participants who would be willing to continue with the next two phases of the study, an in-person focus group and interviews. By choosing to continue participation in the study, principals were willing to discuss the topic of their spirituality among peers.

Data Analysis Focus Group

Principals answering strongly agree or agree were invited to form a focus group that was assigned the collaborative task of generating descriptive data and analyzing the relationships found in the data. These principals answering neutral, disagree, or strongly disagree with leadership being a spiritual practice would not be able to elaborate on their spiritual practices; therefore, they were not brought into the focus group. The interactive analysis was facilitated by the researchers, and the interactions were documented. The focus group contributed to the analysis through four processes: a silent nominal group technique, open and axial coding, identifying research affinities, and developing the affinity relationships; each process is defined below. The focus group met in person within four weeks of closing the survey with the date determined based on availability of the participants. The in-person data analysis process took approximately one hour, and norms were established to encourage participation and respect among participants. Local COVID-19 protocols for in-person meetings were also followed.

Silent Nominal Group Technique. The silent nominal group technique allowed for participants to brainstorm on a topic without discussion, to prevent the influence of more dominant members of the focus group. Each participant responded to the prompt: You answered on the survey that spirituality plays a role in leadership practices. We would like to know more about those practices. On your own, without help from others, list eight to ten leadership practices that you believe relate to your spirituality. Use the sticky notes for your brainstorming. Please write one idea per sticky note. Participants were given enough time for most of the group to note eight to ten ideas on the sticky notes. At this point, each participant was given an opportunity to share the ideas they had generated. The sharing process provided a brief recap of the ideas written and was not an opportunity for expanding on answers.

Open Coding and Axial Coding. Open coding was a data analysis method that allowed participants to sort responses. The principals were given the prompt: Thank you for sharing your responses. As you listened to others, did you hear similar responses? Did you hear unique responses? Work together as a team to group the sticky notes, based on similarities. You may have some sticky notes that do not fit in a group; therefore, some groups may be made of a single sticky note. Participants required time to arrange their responses into groups. The researchers facilitated the process; however, the participants analyzed their own data. When the participants completed the open coding of the data, a spokesperson was invited to share the thought processes used to group the responses.

Axial coding required participants to refine and narrow the categories established during open coding. Participants analyzed the relationships among the groups of responses, using the prompt: Now that you have identified the different groups of responses, look for relationships between the groups. Could any of the groups be combined into broader categories? This may require you to remove/add to/revise some of the wording in the responses to clarify big ideas. Work together to clarify the grouping and identify the relationships between the different groups of responses. Collaboratively, participants moved the groups of responses into broader common groups. In this study, open coding of 121 responses from the silent nominal grouping technique resulted in 14 categories of common responses. Axial coding narrowed the 14 open codes into three broad affinity groups. The purpose of axial coding was to construct linkages between the data. During the coding process, the researchers solely facilitated and did not participate in the sorting of responses.

Identifying Research Affinities. Affinities were words used to describe commonalities among the responses. Each grouping of sticky notes represented a socially constructed consensus of meaning. The focus group decided on the words or phrases used to describe the affinities, by following the prompt: Now that we have formed groups of responses that are related, work together to name, or categorize the groups based on the meaning of the groupings. You can use a single word or group of words to name the groups. The names given to the different groupings were called affinities. These affinities formed the definition of spiritual leadership practices for this research.

Developing the Affinity Relationships. Finally, the focus group analyzed the affinities through directional coding to demonstrate the relationships among the affinities. Directional arrows were used to show influence of the relationships. For example, an arrow from Affinity #1 to Affinity #2 showed that Affinity #1 influenced Affinity #2.

Interviews

Each member of the focus group was interviewed using a protocol, developed based on the affinities and relationships identified among them defined by the focus group. The interviews served as a tool to collect additional data related to inputs and outputs and perceptual data on how spiritual leadership actions influenced the behavior of others. Principals were asked to describe what each affinity, as defined by the focus group, looked like in their leadership practices. Additional probing questions generated more specific examples. Finally, the participants described their perceived influence of the affinities on the behavior of others on campus. The interviews were conducted using the Zoom video conferencing platform, at a time determined by each principal and the researchers. Each interview was recorded on audio and transcribed by a third party. The interviews took place within two weeks of completion of the data analysis focus group and were approximately 20 minutes long for each participant. The researchers coded participant interview responses and organized those codes into frequency distribution tables.

Findings

The findings of the study are presented in two sub-sections: spiritual leadership affinities and spiritual leadership practices. These two sub-sections will define the characteristics of spiritual leadership in schools in terms of both words and actions. The data were collected through an interactive qualitative analysis and follow-on interviews. The participant analysis determined the themes that emerged. The interviews served as the descriptive portion of the analysis. The rigor of qualitative analysis depended on presenting factual descriptive data, often called “thick data,” so that others reading the results can comprehend and interpret independently (Ponterotto, 2006). The interviews of the principals described the spiritual leadership practices related to the affinities developed by the focus group.

Spiritual Leadership Affinities

The first part of the data analysis aimed to answer the research question: What are the affinities (categories) of spiritual practices among principals? Interactive Qualitative Analysis processes were used to collect, code, and analyze data to produce affinities. First, the focus group responded to the prompt: list eight to ten leadership practices that you believe relate to your spirituality. The focus group members individually generated 121 responses. Next, the responses were open-coded creating 14 categories. These 14 categories were further coded to identify three affinities of spiritual leadership: belief in a higher purpose, personal values, and interpersonal relationships. Table 1 details the coding scheme.

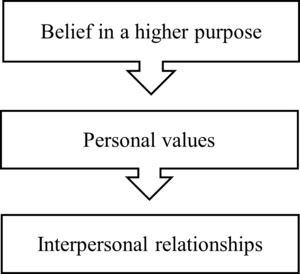

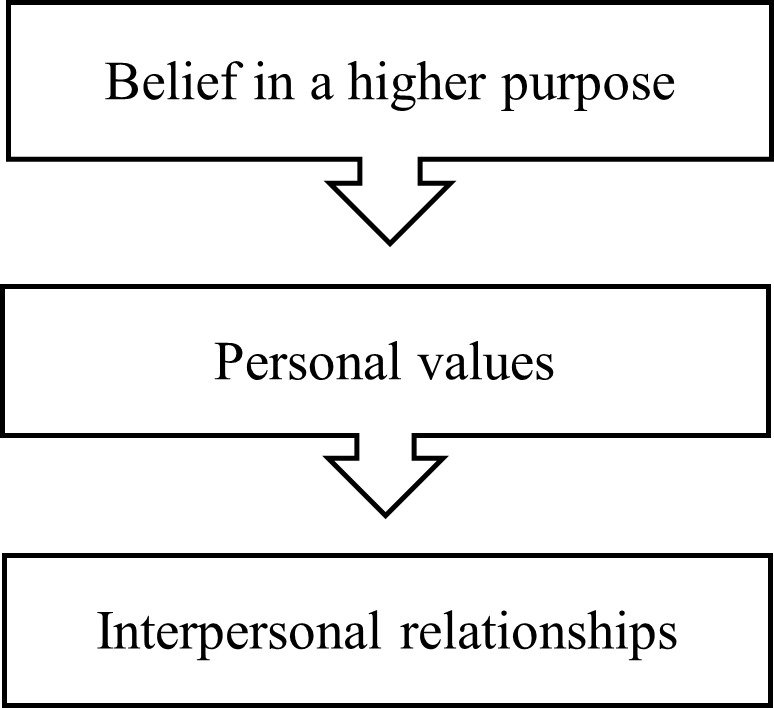

Once the affinities were identified, the focus group was then asked to describe the relationship among the affinities using the concept of directionality. They described belief in a higher purpose as the apex of spiritual leadership. The belief in a higher purpose then influenced their personal values, that influenced their interpersonal relationships. Figure 1 visualizes the relationships described by the focus group.

Spiritual Leadership Practices

Descriptive data were collected through semi-structured interviews. The descriptive results served to answer the research questions: what is the relationship between these affinities and leadership actions, and how do principals perceive the influence of spiritual leadership on the behavior of others? Participants were asked to describe leadership practices related to the three affinities. They were also asked how they perceived the influence of spiritual leadership practices upon others. The principals were given pseudonyms using the alphabet A through J. Principal A is referred to as PA, Principal B is referred to as PB, and so on. The pseudonyms were used to code data from the interviews. The significant findings from the interviews could be summarized into three leadership practices: creating membership, taking pause, and purposefully communicating.

Belief in a Higher Purpose

The interviews began with commentary about the affinity: belief in a higher purpose; however, the conversation about purpose started during the focus group. While coding responses, participants described their job as principal as more than the technical day-to-day running of a school. They shared that this affinity is really about our reason for being, the purpose of life. The interviews revealed their connections with the idea of higher purpose.

A frequency distribution of their responses from the interviews is displayed in Table 2 showing the most frequently referenced topic being membership shared by eight of ten participants. Principals described the topic of membership in various ways; however, in general, principals described membership as the importance of people being connected. Many principals described membership through a relationship with one of the other topics. PB explained the relationship between membership and love, “We have a responsibility to love one another–students, staff, parents, community. Our higher calling is to love others.” While the frequency of care for others was only two, PD related the actions of care for others to membership, “I have been called to care for people. I don’t know everything. I am not great at everything. But I do try to care for people with my whole being.” PJ connected personal background of being raised by a single dad to membership, “I was raised by a single dad. People invested in me, and I want to give back. I want families to know that it does not matter what your background is, our campus will be there for you.” To remaining focused on a higher purpose, principal responses revealed a clear leadership practice of creating membership through actions such as letting others know they are loved, caring for others, and acceptance.

Personal Values

While coding responses in the data analysis focus group, principals made a connection between the first and second affinities. They concluded that believing in a higher purpose informs personal values. During the interviews, principals described the practices they implement to stay true to their personal values.

The topic of pause was most frequently mentioned in eight of ten interviews. The frequency of the other topics discussed related to personal values are displayed in Table 3. Pausing allowed principals to seek guidance through prayer, daily readings, and networks of colleagues, among other connections. PB used pause and prayer as an anchor to fight off cynicism, “We are living in a very tough time that is full of finger pointing and placing blame. It is easy to become cynical. Prayer is how I keep from becoming cynical.” Pause and a reminder of grace was identified as a leadership action for PC, “I have to step back when I begin to get frustrated with others on campus. I remind myself that I need grace daily. I need to extend grace to others.” Pause and gratitude were also connected throughout the interviews. PE found gratitude through the pause of evening walks, “I make myself go home and walk every night. I focus on something that God has created and be grateful for that. It gives me peace. I start the next day with more gratitude.” The leadership action of pause was a central topic during the principal interviews. They used the practice of pause to strengthen their personal values like, happiness, grace, and gratitude.

Interpersonal Relationships

The third affinity, interpersonal relationships, was generally described by the principals as how we treat others. Table 4 displays the frequency of topics from the interviews when the principals were asked about interpersonal relationships. Communication was mentioned most frequently in eight of ten interviews. Many of the principals emphasized that communication starts with listening. PH commented, “Ask a meaningful question and listen. Listen to the whole response. This requires empathy.” They also described the importance of taking time to communicate through writing. PC gave the example, “I write notes to my staff. Sometimes it is just a little celebration or word of encouragement.” Principals connected communication throughout the other topics referenced in the interviews. For example, servant leadership practices were described by the majority of the principals, yet the reason for being a servant leader often related back to a form of communication. PE stated, “My actions speak louder than my words. I ask for my staff to do hard things, but I never ask them to do something I am not willing to do myself.” How we communicate was identified as an important leadership action, though what we communicate held importance for the principals, as well. Share faith was a topic referenced during the interviews in the other affinities; however, share faith was a strong theme, referenced six times for this affinity. PI indicated, “I am careful not to share my specific faith, but I remind people that we have a higher calling.”

Influence Upon Others

The interviews culminated in the question about the principals’ perceptions of whether these spiritual leadership practices had an influence on the behavior of others. The most common response initially was I do not know, but I hope so. This question required more prompting than the previous questions; however, the principals provided numerous examples after some reflection.

PI: Forgiveness is becoming part of our culture. I can see it in the way teachers talk with students and parents.

PG: I believe encouragement rubs off on my staff and the kids. Their words of affirmation certainly encourage me to do more.

PF: Being a servant leader is important. Just this week I had to serve meals in the cafeteria because we were short staffed. Helping in the cafeteria, wiping tables, sweeping a mess – that is all servant leadership. And my staff is good to pitch in when we need additional help. They see me do it and they know that is just what we do.

PE: I am so proud because I think grown-ups here model servant leadership and kids do as well. It’s contagious.

PD: When we share our faith it holds us accountable to each other – we listen, we offer forgiveness, we show respect to others.

PA: If my campus understands we are all here for a common purpose, then when one of us struggle we know it is our responsibility to be there for each other. Needing help isn’t a negative thing. When I as the leader make a mistake, I own it publicly. I think we are getting better at just acknowledging a mistake and moving on.

Research Questions

Is leadership a spiritual practice and if so, to what extent? Of those principals who completed the initial survey, 85% agreed or strongly agreed that leadership is a spiritual practice. This validated the findings of Woods (2007) that spiritual experiences among principals are widespread. Throughout this process other principals who had learned of the study asked if they could be included in future conversations about spiritual leadership. This could be considered further evidence that this topic is relevant and has a wide reach. If principals broadly share a belief in spiritual leadership, then the natural progression of thought leads to the second research question.

What are the affinities (categories) of spiritual practices among principals? An in-person data analysis focus group answered the second research question. The 14 principals brainstormed, discussed, and coded responses to identify the affinities of spiritual practices. The focus group narrowed 121 individual responses to 14 categories to 3 affinities: belief in a higher purpose, personal values, and interpersonal relationships. Their coding reflected the Gibson (2014) case study that described spirituality as having internal dimensions in terms of beliefs, values, and external applications pertaining to relationships. The focus group displayed the relationship between the affinities in a linear path. They explained that our beliefs in a higher purpose define our personal values, and those values influence the interactions we have with others.

The focus group benefitted from their social interactions. Through their conversations, this group of principals recognized they share a common purpose. They began asking questions of each other and sharing practices. By simply participating in the interactive data analysis, principals reported heightened spiritual connections. Although the conversations were meaningful, the principals were asked to continue coding to complete the analysis and expressed eagerness to read the final analysis. The interest in learning from each other further underscores the concept that effective leaders understand the value in spiritual teachings (Reave, 2005).

What is the relationship between these affinities and leadership actions? Semi-structured interviews provided an opportunity for principals to give examples of leadership practices related to the three affinities. Although the interviews took place through an online video platform and had a formal format, the participants seemed immediately at ease. They openly shared stories of faith, difficult childhoods, professional failures, and personal struggles. The willingness of the participants to freely share in the interviews could support the theory presented by Yang et al. (2019) asserting that spiritual leaders’ focus on purpose and meaning can positively impact the climate of an organization. The interviews revealed a focus on three leadership practices: creating membership, taking pause, and purposefully communicating.

Spiritual leaders create membership. They build campus communities where people feel connected by a common purpose. This supported the theory Fry (2003) introduced wherein spiritual leaders motivate others through a sense of calling and membership. The principal interviews revealed that spiritual leaders who believe in a higher calling were focused on helping students, teachers, parents, and community members feel like they belong and are appreciated.

Spiritual leaders find power in pause. They know the importance of slowing down to seek guidance. The interviews revealed the business of being a principal. They shared stories of juggling responsibilities and late night or weekend work. When they were asked about practices they use to maintain their personal values, they described different ways to pause. Some took walks, some read, others would sit on the side of the bed for a few minutes in the morning to find gratitude, and many referenced prayer. Regardless of how they decided to pause, the purpose seemed to be about recentering on the higher purpose and recommitting to personal values.

Spiritual leaders value purposeful communication. Zohar (2005) identified traits of spiritually intelligent leaders and found that they ask deeper ‘why’ questions and listen to understand the wider context. The principal responses supported Zohar’s findings. They practiced asking meaningful questions and genuinely listened with empathy. The principals also regularly reminded people of the higher purpose of the work through personal interactions, faculty meetings, and written correspondence.

How do principals perceive the influence of spiritual leadership upon the behavior of others? This research question was focused on principal perception. The interviews bogged down here. The principals, in general, were unsure if their spiritual leadership practices influenced the behavior of others. Follow-up probing questions helped them make connections or gave them time to recall examples. This is an area worthy of additional study.

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of the study was the collaborative nature of IQA. The participants were able to learn with and from each other to identify the affinities. The interactions in the focus group appeared to create a sense of trust with the participants that contributed to the quality of responses in the interviews. Additionally, the topic itself was a strength of the study. Principals who participated seemed genuinely engaged in the conversations and curious about the findings. Interest from principals beyond those participating in the study also indicated the opportunity to replicate the study.

The limitations of this study included the population sampled and the accuracy of self-reported data. The sample in the present study was from a regional area of Texas where 80.3% of the population identifies as Christian and 42% of the population attends church services at least weekly (The Association of Religion Data Archives, 2010). Generalizability of the study would be limited based on the regional population sampled and indicate a need for future studies with different locations and demographics of school leaders. In addition, self-reported data from school leaders may not accurately reflect the perception of teachers on campus.

Implications

The research presented has significant implications in four areas: research design, recruitment and hiring, professional development, and further study.

Implications for research design

-

Qualitative researchers who are comfortable facilitating processes should consider using IQA. The participants shared meaningful dialogue that informed the study.

-

The interactive focus group analyzed a very complex subject and gave the researchers lay persons’ perspectives and definitions.

-

The community building in the focus group contributed to an open, friendly interview climate.

Implications for recruitment and hiring

-

This research suggests the recommendation that organizations should select individuals with characteristics and values that predispose them to spiritual leadership (Wang et al., 2019).

-

Human resource directors should consider designing interview questions that encourage responses related to the three affinities: What do you believe is your higher purpose for being a principal? What are some of your personal values? How do those values influence your relationships with others?

-

Future principals are classroom teachers today. Consider using interview questions with a spiritual component when hiring teachers.

-

Consider reviewing principal evaluation systems for themes identified in this research: membership, pause, and purposeful communication.

Implications for professional development

-

Provide leadership training that focuses on beliefs in a higher purpose, personal values, and interpersonal relationships expanding the toolkit for principal practices.

-

Provide opportunity for leaders to examine complex situations with others through a spiritual lens.

-

Use IQA to help unpack complex problems.

Implications for further study

-

Study the differences in perceptions of influence of spiritual leadership practices upon others. If the principal has a higher calling to create membership on campus, do students form social groups differently? If the principal models the importance of pause, do teachers see the value of pause during instruction? If principals focus on asking better questions and pay attention to the answers, do parent meetings function differently?

-

Validate this study by replicating it across broader ranges of schools and across various geographic regions.

-

Explore the relationship of spiritual leadership and school performance.

-

Further investigate leadership practices for those participants who answered neutral, disagree, or strongly disagree on the survey.

Discussion and Conclusion

Spirituality plays an integral role in the leadership practices of educators and presents an important and valuable topic for research. Through a deeper understanding of who we are as leaders and how that actually impacts what we do, educational leaders may be better equipped to influence human behaviors. In affirmation of previous studies, spiritual leadership highlights our own humanity and connections to the world around us. Pearce (2007) suggested leadership development should be more comprehensive and include spirituality and a broader set of behaviors. Aydin & Ceylon (2009) characterized spiritual leadership as defending integrity and strengthening goodness and interconnectedness while Pio & Lengkong (2020) determined that increased spiritual leadership influenced increased ethical behaviors among the people they led. The relationship between spirituality and leadership demonstrates a correlation with the spiritual practices of educational leaders that influences and impacts human behaviors within their organizations. The findings of this study clearly identified three affinities of spiritual leadership and how they are interrelated: belief in a higher purpose, personal values, and interpersonal relationships. When we understand that life has a higher purpose, then our personal values should reflect that higher purpose and our personal values influence how we treat others.